Poverty and education — most non-genetic health issues can be traced back to those two factors.

The poorer and less educated you are, the harder it is to stay healthy.

It’s not a new problem.

In 1980, the average life expectancy in the U.S. reached 74 years, yet certain pockets of the population, including African-Americans, Latinos and Asian-Americans, continued to live shorter lives.

Minorities had higher rates of diabetes, cancer, heart disease, stroke, substance abuse and infant mortality. Over the last few decades those rates have decreased, but one thing remains the same: minorities still aren’t as healthy as the population at large.

What’s happening

“Health outcomes for minorities in Tennessee are substantially poorer due to high blood pressure, asthma and coronary artery disease,” says Rafielle Freeman, Director of Quality Improvement at BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee. “We also see shocking rates of homelessness and poverty in minority populations.”

More than 8,300 Tennesseans experienced homelessness last year, and nearly 16 percent of Tennesseans live in poverty.

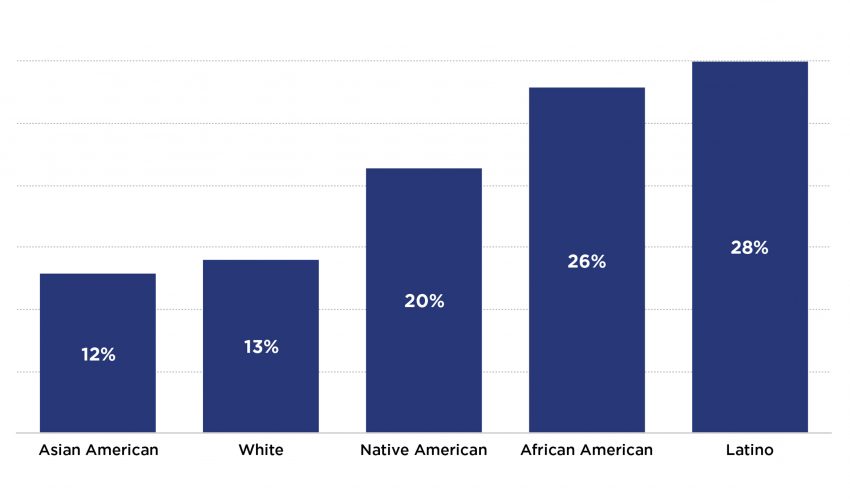

Of those in poverty:

- 12% are Asian-American

- 13% are White

- 20% are Native American

- 26% are African-American, and

- 28% are Latino.

With poverty comes health challenges: a lack of secure housing, unsafe neighborhoods and limited access to healthy foods and transportation. Add in lower levels of education — one of the best predictors of lifetime health — and you have an environment that is all but guaranteed to create unhealthy cycles.

“We see these issues all over Tennessee but particularly in rural East Tennessee and urban West Tennessee,” says Freeman. “Since Memphis is my hometown, it’s even more personal to me to help make sure things change.”

Tennesseans in poverty by race, 2017

So where do we start?

For Freeman, it’s easy: go there.

“You can’t sit in a building and change poverty if you’ve never seen it,” she says.

So she took her team to 38109 — a ZIP code in Memphis that geo-mapping identifies as a food desert with poor transportation. When subsidized housing was shut down in the area a few years ago, people got pushed out, and the situation got worse.

“When you go out there, you see no grocery stores, boarded-up houses, children walking around without parents, men who are standing on the corner not working. They have no playgrounds, no grass; just dirt,” she says.

“I took my staff out there and said, ‘Let me let you see what folks in Memphis are dealing with. Would you let your kids run around this way?’ Without seeing it, I think people underestimate the struggle of people in need. You have to connect with a community to understand it.”

Once that connection is established, Freeman says there are tools in place to help people access the resources they need.

- In 2010, the Healthy People 2020 initiative established science-based, 10-year national objectives for improving the health of all Americans, and they provide resources to help communities do that.

- In Tennessee, the United Way connects people with resources through 2-1-1.

- In Memphis, the Community Alliance for the Homeless and Shelby County Health Department are partnering to address poverty, homelessness and health.

Click the image above to read observations from a health industry panel discussion on diversity in Memphis in 2017.

Coming to an understanding

At all levels, empathy is important, Freeman says. Many of the people she’s trying to help don’t even know they’re struggling — “They just live in this world.” — and she believes you have to understand people before you can help them. She often asks her staff to envision their lives differently.

“Imagine you are someone in poverty with three kids, one of whom is disabled, and you have no transportation,” she asks. “How do you feel?”

She gives her staff shortcuts for gaining perspective, one of which is doing five things when talking to people:

- Listen with undivided attention

- Reflect on what people say before you respond

- Validate how the other person is feeling

- Find and respect that person’s strengths, and

- Create a partnership to help them solve their problem.

“We know that not everybody understands what it means to be in poverty, or to have a child with a disability, or to be battling mental health issues,” she says.

“But we also know that these issues are prevalent in Tennessee, so really everyone knows someone who’s struggling with something.

“We all have to be passionate about working toward our ultimate goal: no closed doors.”